Routing Technologies

Static Routing

Routing Tables

The router has a relatively simple job

- The underlying technology is relatively complex

Identify the destination IP address

- It’s in the packet

If the destination IP address is on a locally connected subnet

- Forward the packet to the local device

If the destination IP address is on a remote subnet

- Forward to the next-hop router/gateway

- This “map” of forwarding locations is the routing table

Static Routing

Administratively define the routes

- You are in control

Advantages

- Easy to configure and manage on smaller networks

- No overhead from routing protocols (CPU, memory, bandwidth)

- Easy to configure on stub networks (only one way out)

- More secure — no routing protocols to analyze

Disadvantages

- Difficult to administer on larger networks

- No automatic method to prevent routing loops

- If there’s network change, you have to manually update the routes

- No automatic rerouting if an outage occurs

Dynamic Routing

Routers send routes to other routers

- Routing tables are update in (almost) real-time

Advantages

- No manual route calculations or management

- New routes are populated automatically

- Very scalable

Disadvantages

- Some router overhead required (CPU, memory, bandwidth)

- Requires some initial configuration to work properly

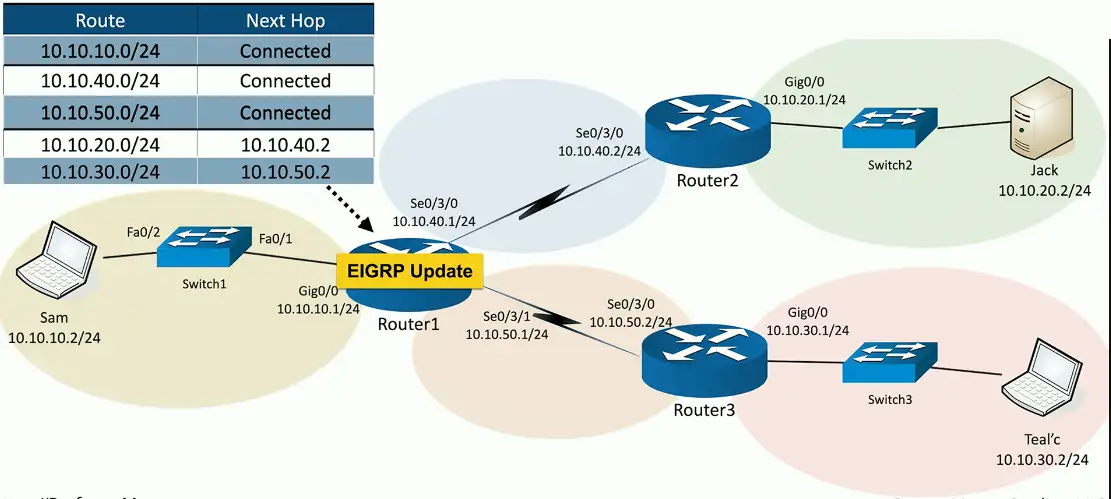

EIGRP Update

- Enhanced Interior Gateway Routing Protocol

- EIGRP is used to exchange routing information between routers

- CISCO controlled proprietary protocol

- Not widely adopted except on Cisco and partners devices

OSPF

- Open Shortest Path First

- It is a link-state routing protocol used to calculate the best path for data transmission within an IP network

- Fully open standard

- Vendor neutral

Dynamic Routing Protocols

Listen for subnet information from other routers

- Sent from router to router

Provide subnet information to other routers

- Tell other routers what you know

Determine the best path based on this information

- Every routing protocol has its own way of doing this

When network changes occur, update the available routes

- Different convergence process for every dynamic routing protocol

Which routing protocol to use?

What exactly is a route?

- Is it based on the state of the link?

- Is it based on how far away it is?

How does the protocol determine the best path?

- Some formula is applied to the criteria to create a metric

- Rank the routes from best to worst

Recover after a change to the network

- Convergence time can vary widely between routing protocols

Standard or proprietary protocol?

- OSPF and BGP are standards, some functions of EIGRP are Cisco proprietary

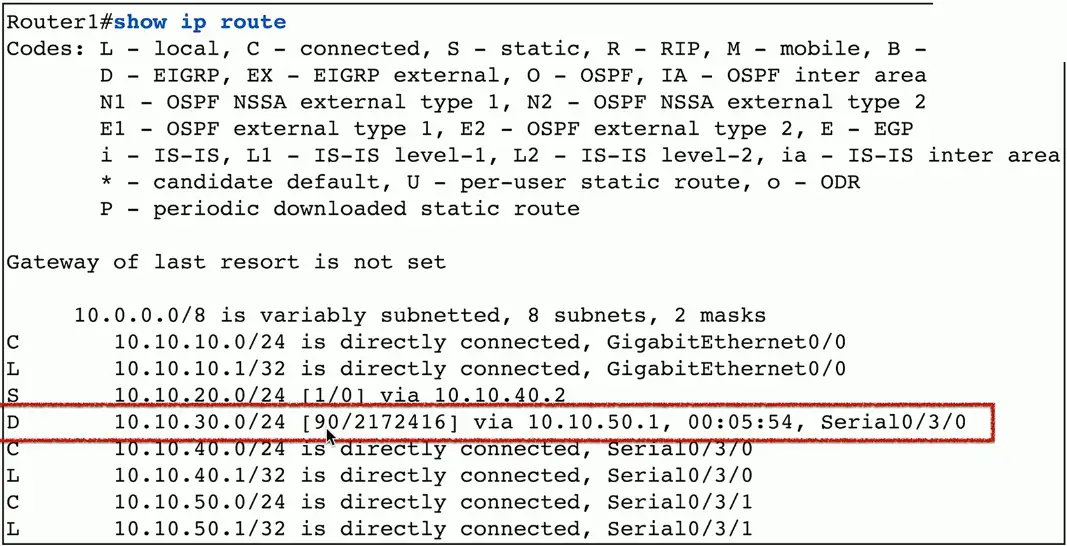

Enhanced Interior Gateway Routing Protocol

EIGRP

- Partly proprietary to Cisco

- Commonly used on internal Cisco-routed networks

- Relatively easy to enable and use

Cleanly manage topology changes

- Speed of convergence is always a concern

- Loop free operation

Minimize bandwidth use

- Efficient discovery of neighbor routers

OSPF

Open Shortest Path First

- A common interior gateway protocol

- Used within a single autonomous system (AS)

A well-established standard

- Available on routers from many manufacturers

Link-state protocol

- Routing is based on the connectivity between routers

- Each link has a “cost”

- Throughput, reliability, round-trip time

- Low cost and fastest path wins, identical costs are load balanced

BGP (Border Gateway Protocol)

Exterior gateway protocol

- Connect different autonomous system (AS)

The “three-napkins protocol”

- Sketched out to solve an immediate problem

- Turned into one of the most popular

A popular standard

- Used around the world for Internet routing

Routing Technologies

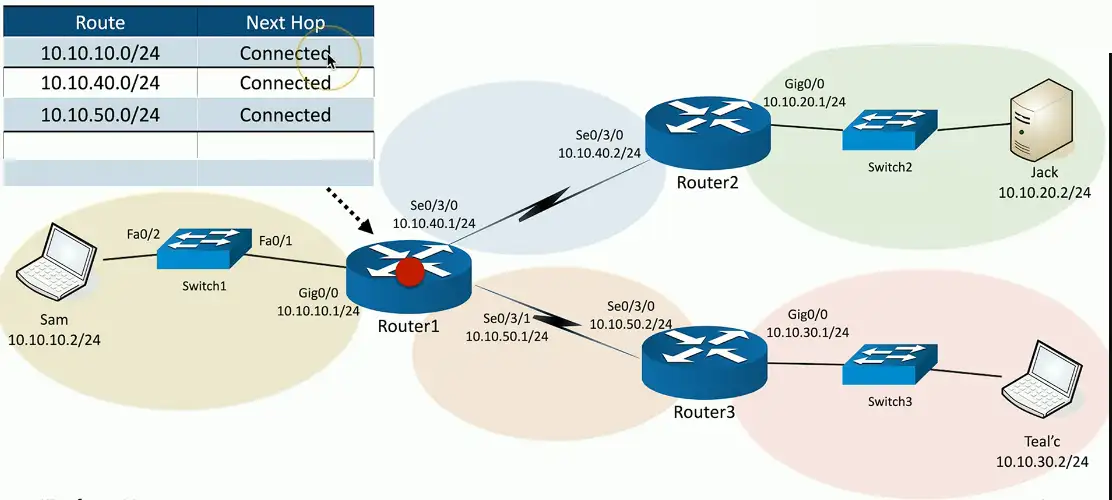

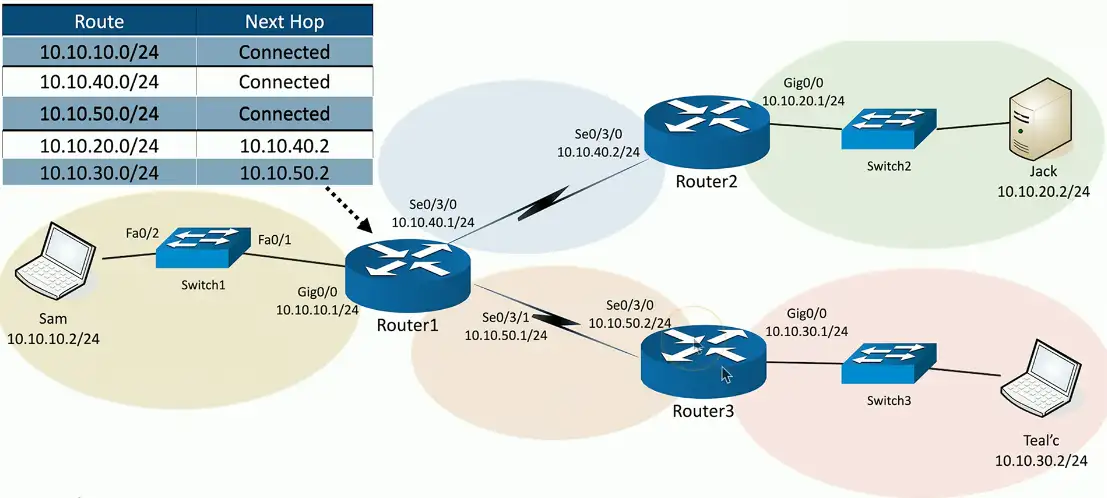

Building a routing table

Routers are digital direction sign

- How to I get to Google? Go that way.

Every IP device has a routing table

- Workstations, servers, routers, etc.

The list of directions is the routing table

- The most specific route “wins”

Sometimes there’s a tie

- Duplicate destinations in the table

- Which do you choose

- There are ways to break the tie

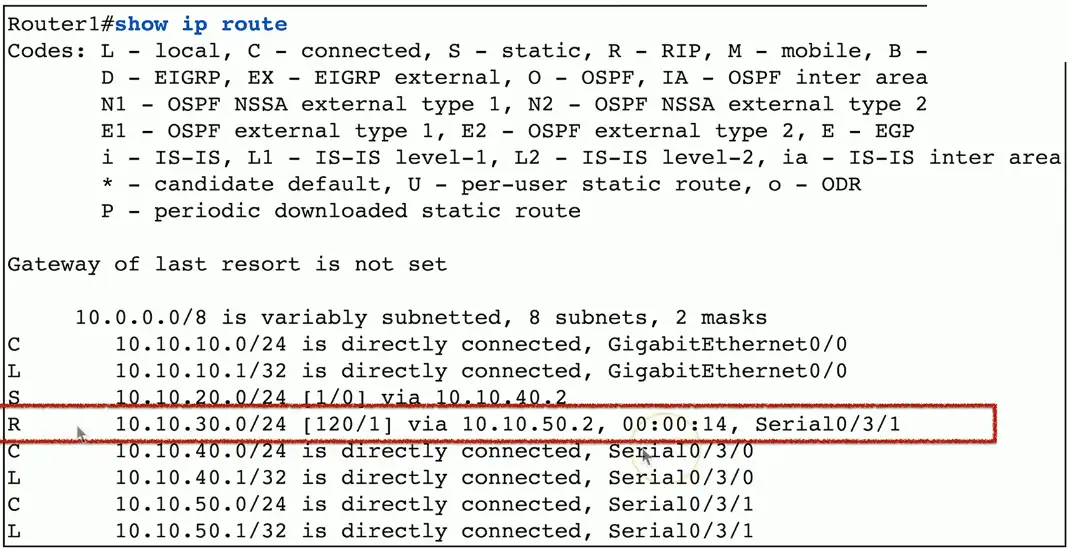

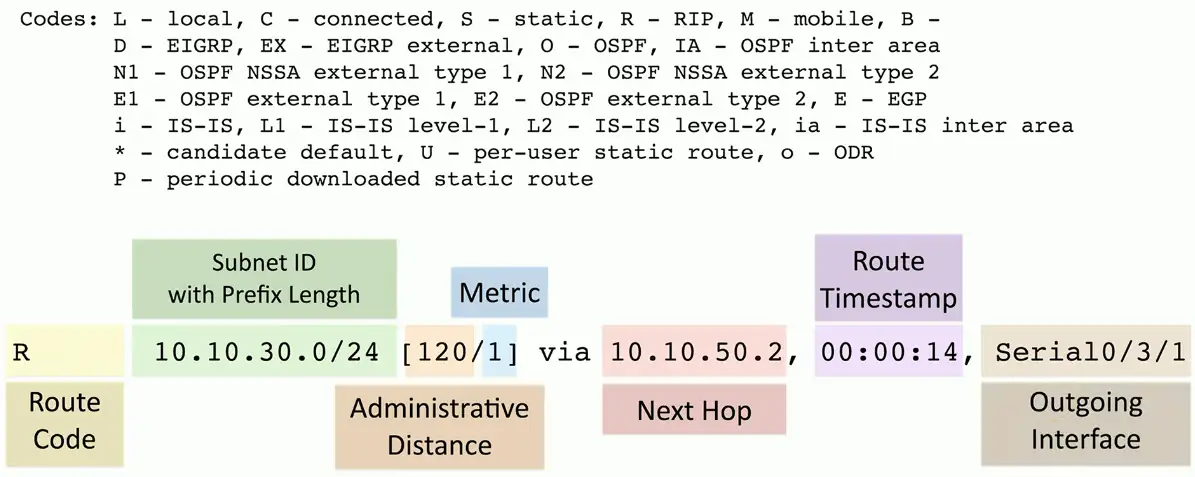

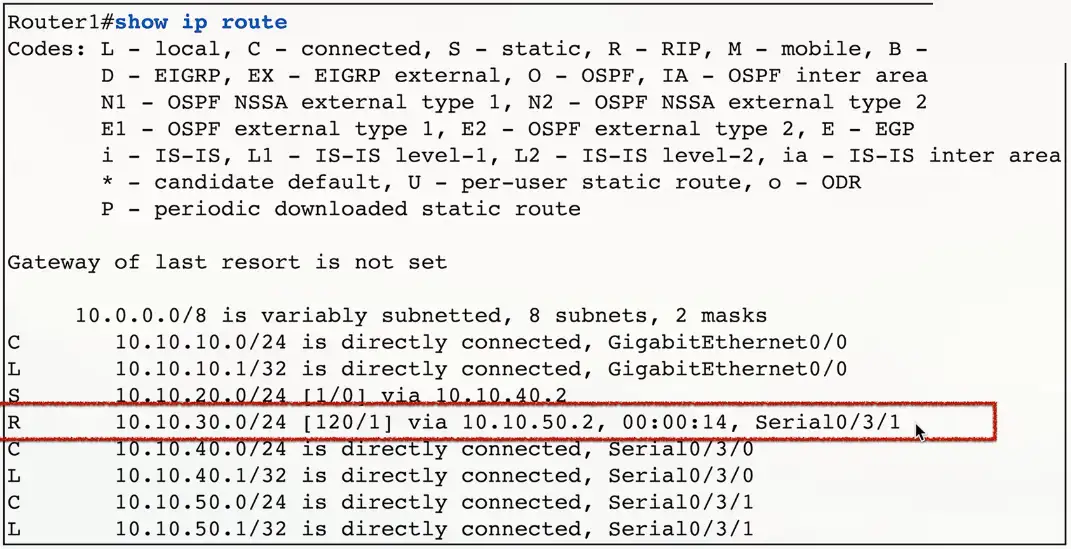

Routing table with RIPv2

Prefix Lengths

Most specific route “wins”

- A combination of the subnet ID and prefix length

Routes are more specific as the prefix increases

- Router forwards traffic to the most specific destination

Pick the best route to a server with the address of 192.168.1.6

- 192.168.0.0/16

- 192.168.1.0/24 (2nd best route with narrow host range than /16)

- 192.168.1.6/32 (Best route, individual IP)

Administrative Distances

What if you have two routing protocols, and both know about a route to a subnet?

- Two routing protocols, two completely different metric calculations

- You can’t compare metrics across routing protocols

- Which do you trust the most?

Administrative distances

- Used by the router to determine which routing protocol has priority

| Source | Administrative Distance |

|---|---|

| Local | 0 |

| Static route | 1 |

| EIGRP | 90 |

| OSPF | 110 |

| RIPv1 and RIPv2 | 120 |

| DHCP default route | 254 |

| Unknown | 255 |

Routing Metrics

Each routing protocol has its own way of calculating the best route

- BGP, OSPF, EIGRP

Metric values are assigned by the routing protocol

- BGP metrics are not useful to OSPF or EIGRP

Use metrics to choose between redundant links

- Choose the lowest metric, i.e., 1 is better than 2

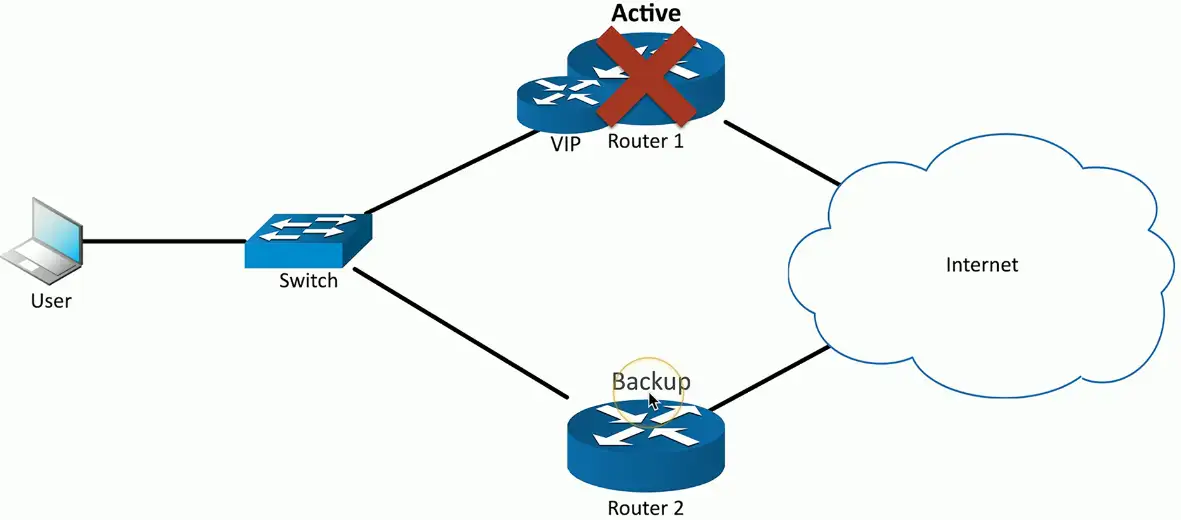

First Hop Redundancy Protocol (FHRP)

Your computer is configured with a single default gateway

- We need a way to provide uptime if the default gateway fails

The default router IP address isn’t real

- Devices use a virtual IP (VIP) for the default gateway

- If a router disappears, another one takes its place

- Data continues to flow

Solves a shortcoming with IP addressing

- One default gateway can really be many routers

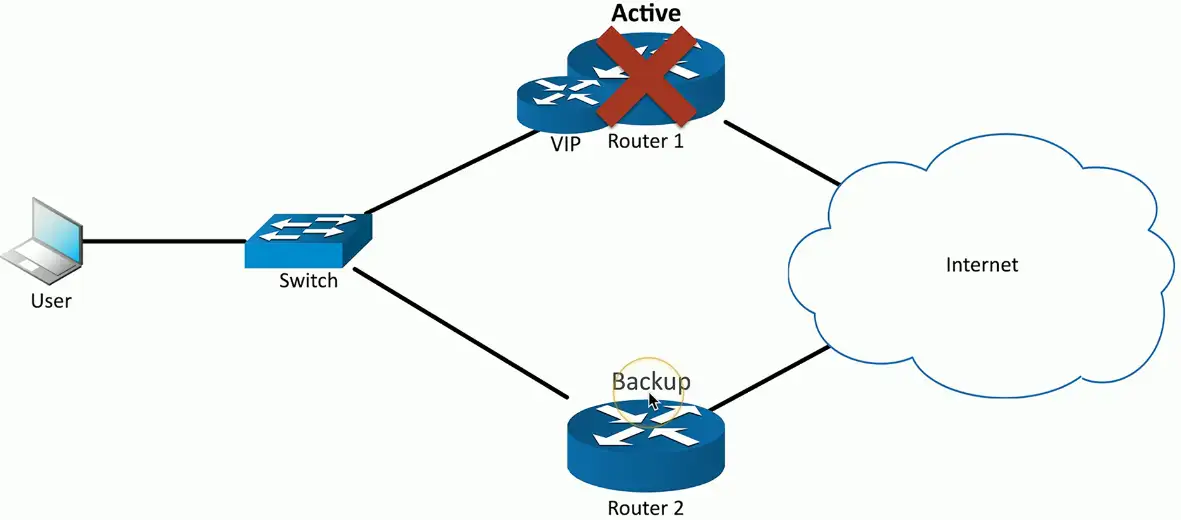

A network with two routers, one acting as a backup, fails:

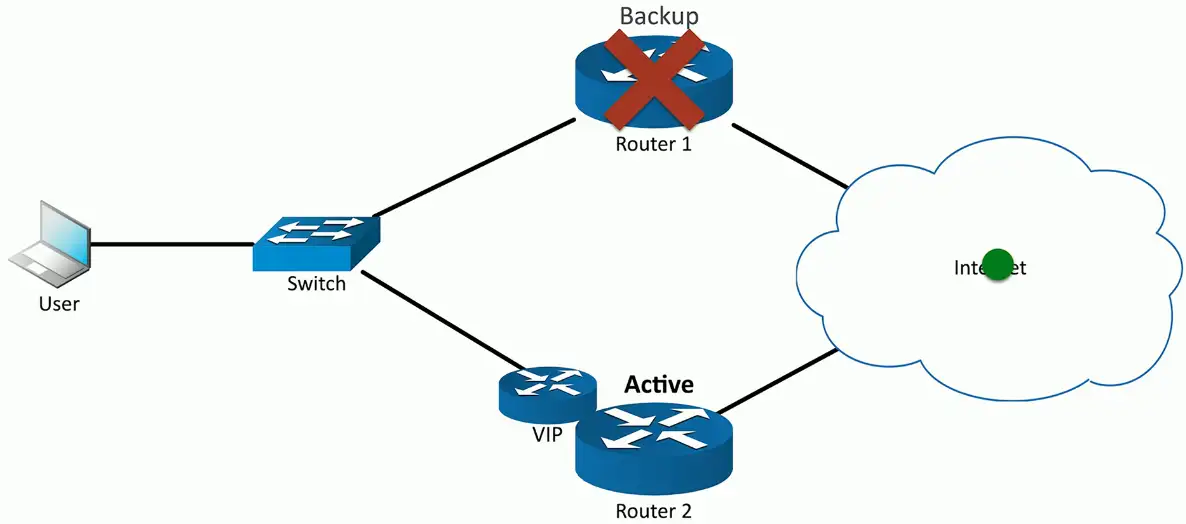

Backup router takes over, and the inactive router will be marked as backup:

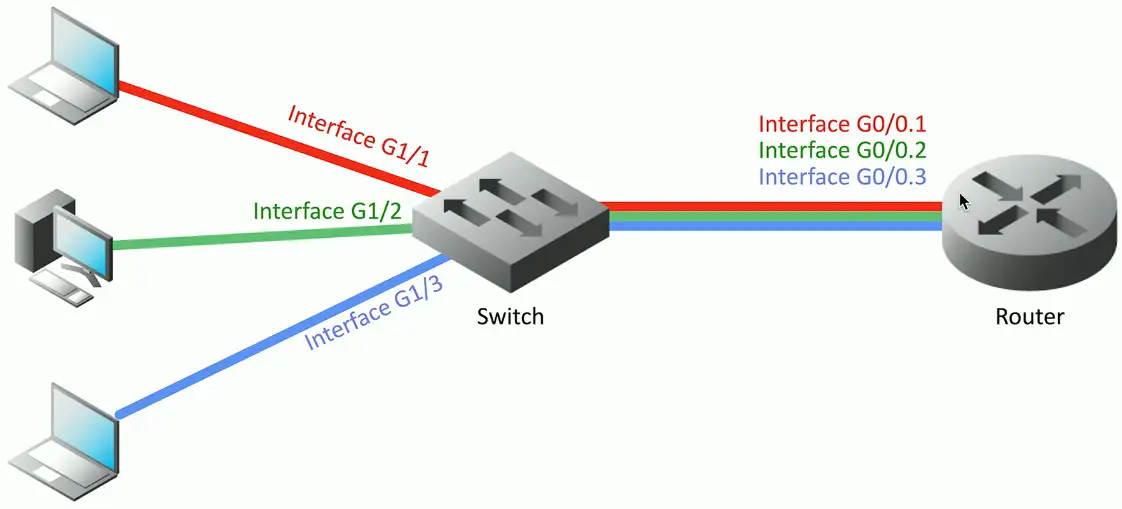

Subinterfaces

A device has a physical interface

- Configure options for each interface

Some interfaces are not physical

- VLANs in a trunk

- These are subinterfaces

Often referenced with the physical

- Interface Ethernet1/1

- Subinterface Ethernet1/1.10

- Subinterface Ethernet1/1.20

- Subinterface Ethernet1/1.100

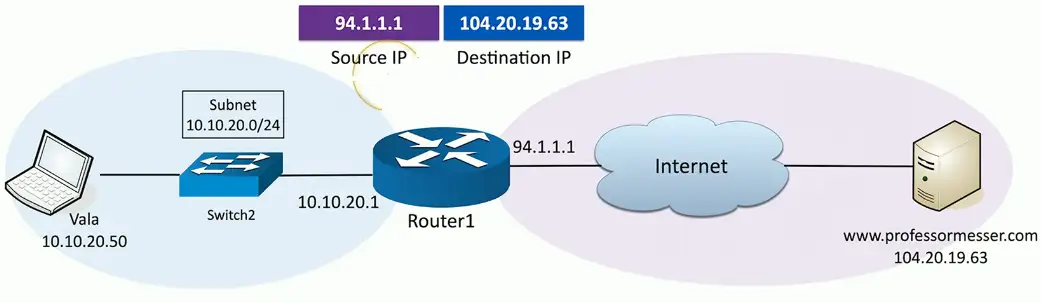

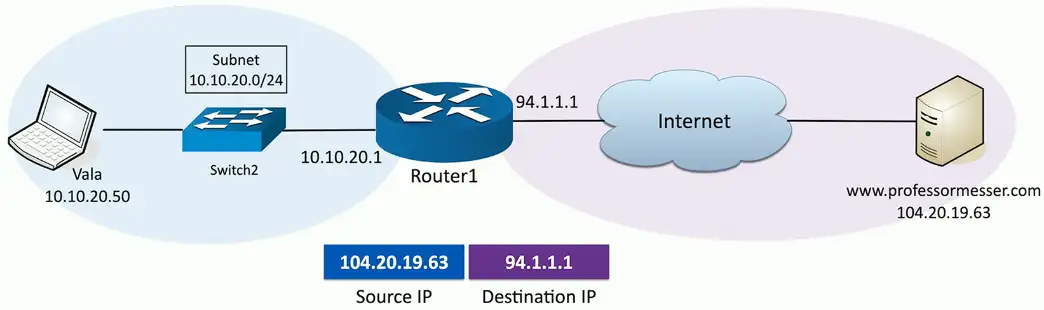

Network Address Translation (NAT)

It is estimated that there are over 20 t 30 billion devices connected to the Internet (and growing)

- IPv4 supports around 4.29 billion addresses

The address space for IPv4 is exhausted

- There are no available addresses to assign

How does it all work?

- Network Address Translation

This isn’t the only use of NAT

- NAT is handy in many situations

Public addresses vs. Private addresses

- RFC 1918 private IPv4 addresses

| IP address range | Number of addresses | Classful description | Largest CIDR block (subnet mask) | Host ID size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10.0.0.0 – 10.255.255.255 | 16,777,216 | single class A | 10.0.0.0/8 (255.0.0.0) | 24 bits |

| 172.16.0.0 – 172.31.255.255 | 1,048,576 | 16 contiguous class Bs | 172.16.0.0/12 (255.240.0.0) | 20 bits |

| 192.168.0.0 – 192.168.255.255 | 65,536 | 256 contiguous class Cs | 192.168.0.0/16 (255.255.0.0) | 16 bits |

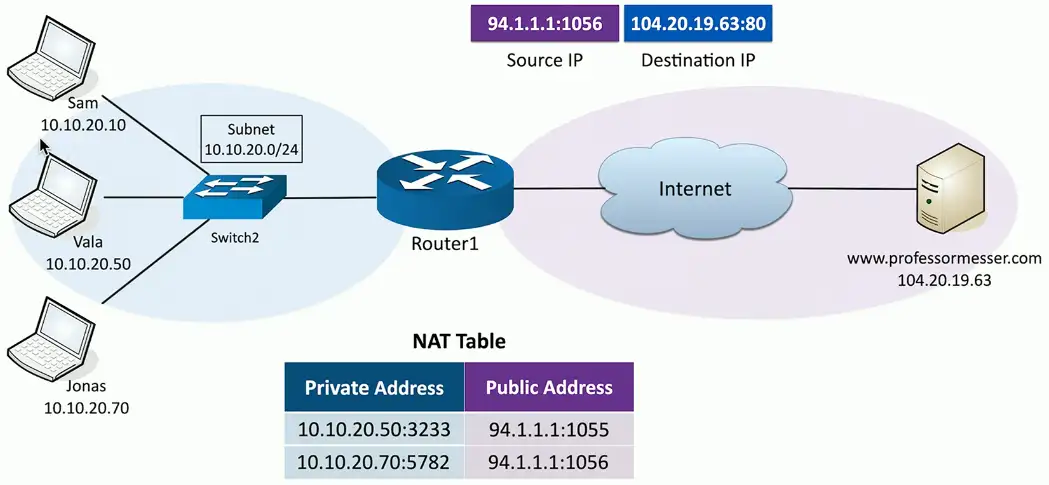

NAT overload/PAT

If we need to perform NAT for many computers on the network at the same, we need more public IP addresses to be available. To do this efficiently, we use NAT overload/PAT (Port Address Translation) protocol.

- More than one device on the network

- Want to reach to the same server on the Internet

- They will be assigned Private Addresses with random port numbers and associated Public IPs with random port numbers.

- The request goes to the destined server with the associated with Public IPs and port numbers.

- The server with respond and router will do the whole process in reverse to direct the server payload to the appropriate client device.